A new tool to help Kentuckians understand benefits cliffs

Workers in low-wage jobs often do not earn enough to make ends meet. As a result, many workers in low-wage jobs rely on public assistance programs to cover the costs of living. These work supports are an important resource for workers in low-wage jobs, helping them afford food, stable housing, healthcare, and childcare.

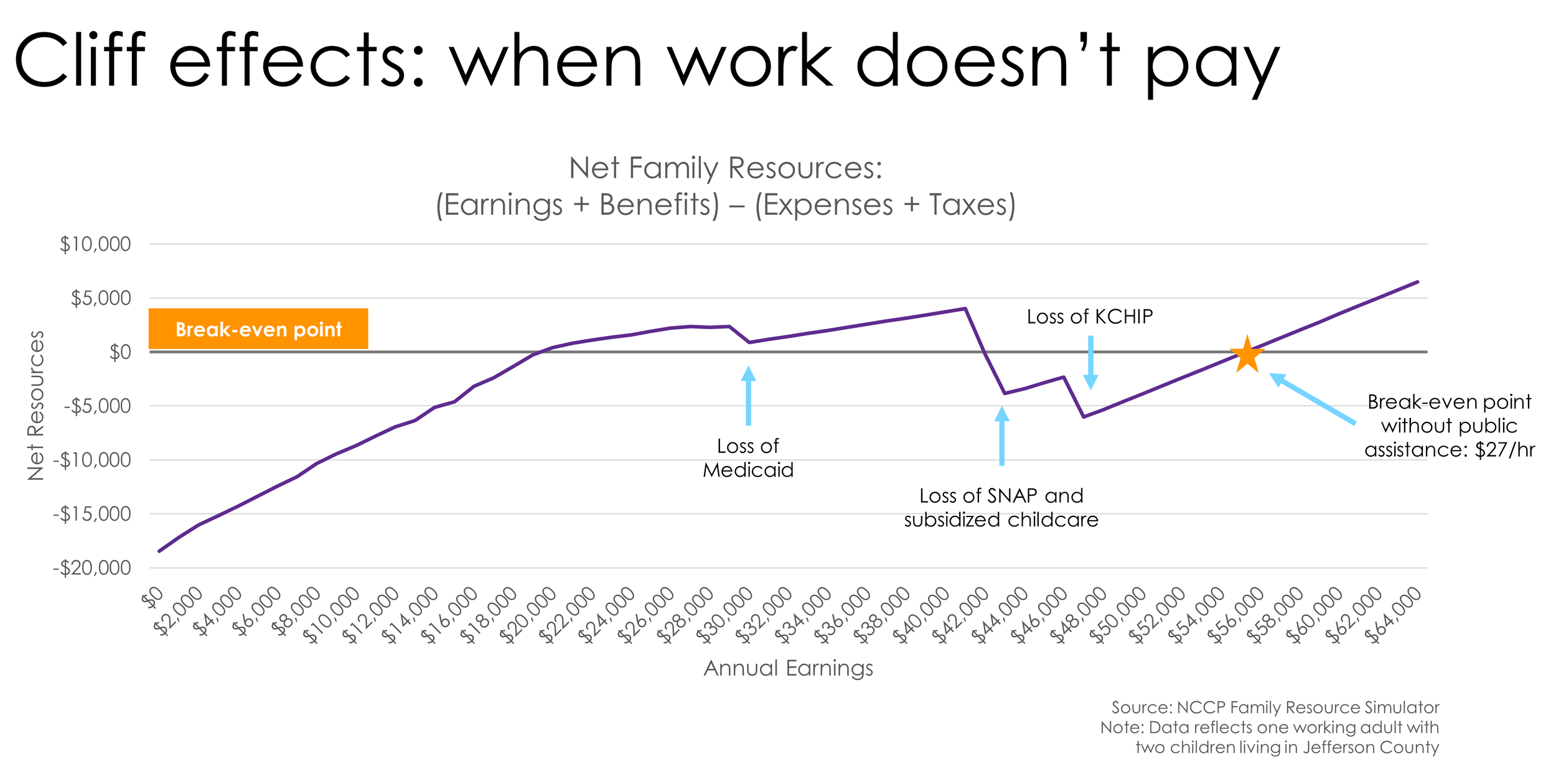

The need for these work supports can lead to tensions in the labor market. Low-wage workers often face trade-offs as they pursue career advancement, because earning more in income can mean losing access to public assistance programs. The Family Resource Simulator is a new tool created by the National Center for Children in Poverty in partnership with the Kentucky Center for Statistics that shows the net result workers face when they earn more but become ineligible for work supports in the process. These cliff effects might prevent workers in low-wage jobs from taking advantage of career advancement because of a very rational decision- they would ultimately have fewer resources to provide for their family.

The entanglement between earned income and work supports provided through public assistance programs is a growing concern, as the number of low-wage jobs continues to increase, as does the cost of living. The disparity between the cost of basic needs and the income needed to cover those costs is a driving factor for why workers in low-wage jobs face cliff effects.

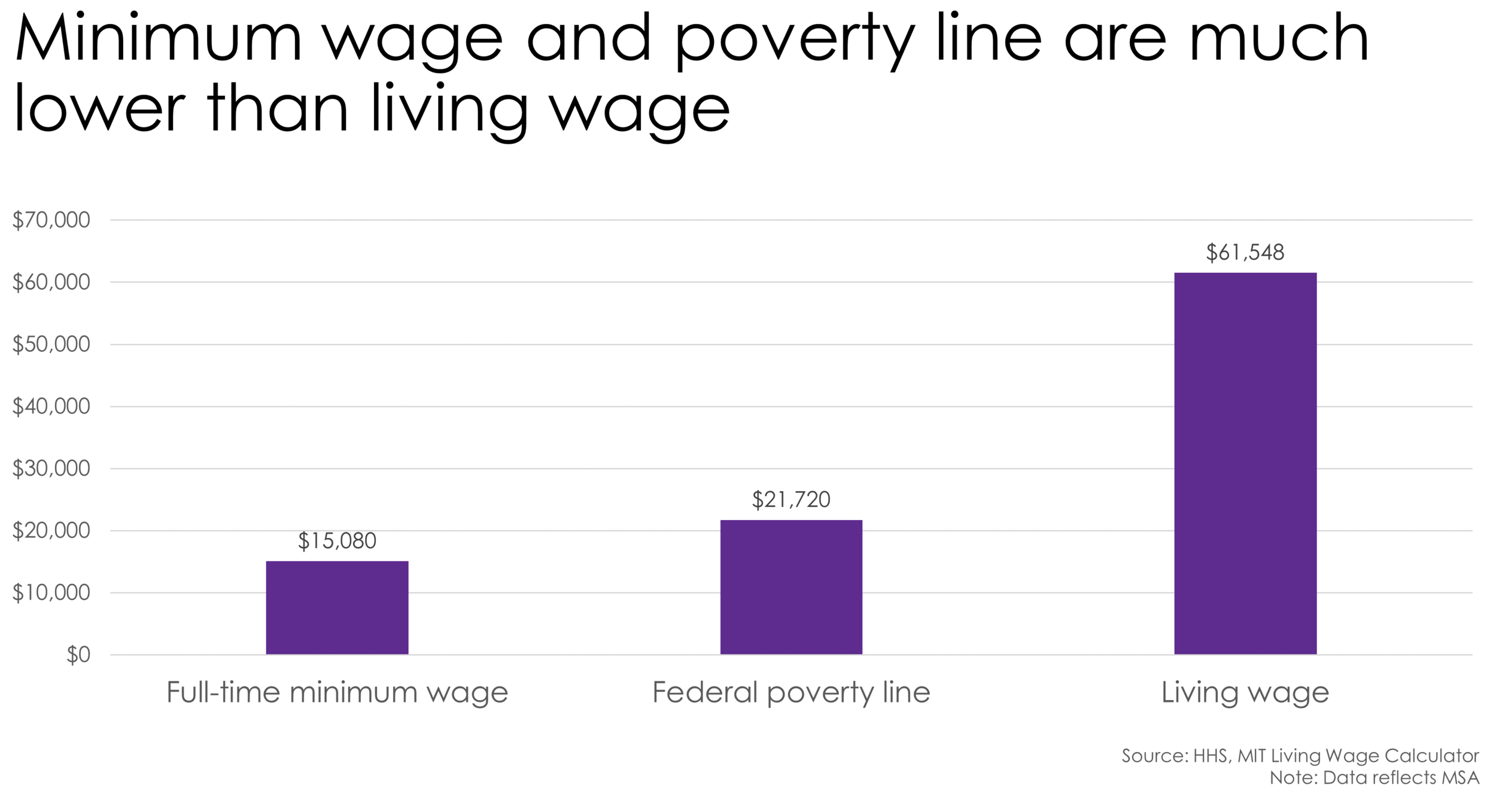

Within the Louisville region, a single mother with two children would need to earn more than $60,000 per year to cover the costs of basic needs for her family, according to the MIT Living Wage Calculator. The Living Wage Calculator does not account for expenses that many families would consider standard enjoyments, such as eating out at restaurants or taking a vacation. It also does not account for any savings or investment, including retirement savings. Rather, the living wage model is the minimum threshold needed to maintain economic self-sufficiency without the use of public assistance programs and without facing severe housing or food insecurity. The authors suggest, “the living wage is perhaps better defined as a minimum subsistence wage for persons living in the United States.”

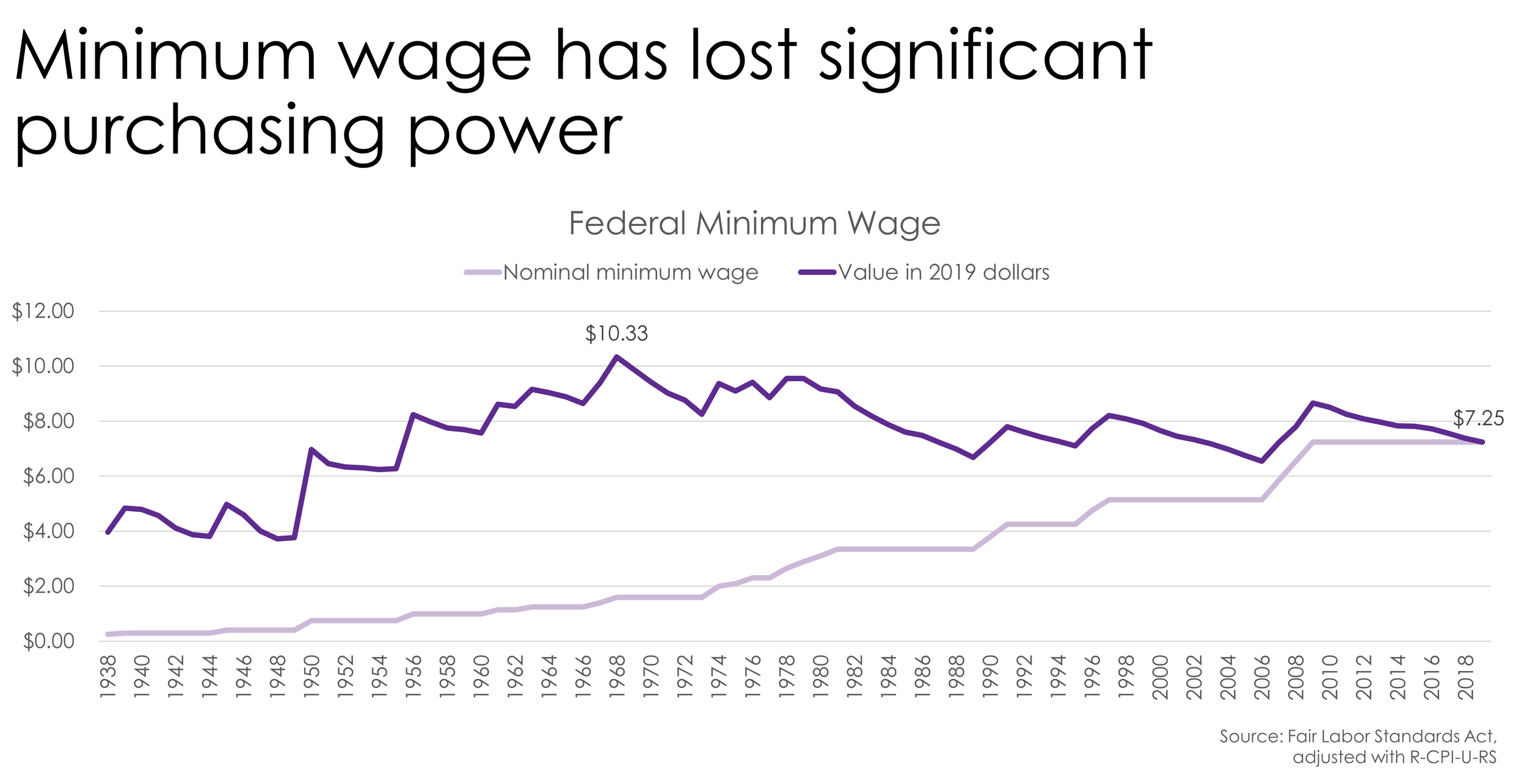

Yet the United States uses other standards to determine what minimum threshold is sufficient for workers. The minimum wage was last increased in 2009. After adjusting for inflation, the current minimum wage is worth 16% less than it was in 2009, and 30% less than its peak value in 1968.

The federal poverty line is often used to determine eligibility for public assistance programs. However, the method used to create poverty guidelines is outdated, and does not account for the current costs of living in the modern economy.

Poverty thresholds were originally established in the 1960s, and relied on data from the 1950s. The 1955 Household Food Consumption Survey showed that the average family spent about one-third of their income on food, and the Department of Agriculture had developed food budgets based on the cost of food in the 1960s. The poverty threshold was therefore established as the lowest-cost food budget, multiplied by three. It has simply been updated for inflation on an annual basis since it’s original establishment. The calculation does not use data based on the current costs of food, housing, childcare, or healthcare. Yet, the federal poverty line is often considered the threshold in which families are deemed to be able to afford a suitable standard of living.

The Living Wage Calculator, on the other hand, uses current, localized data on the costs of basic needs across different geographic areas. The living wage in the Louisville region for a single mother with two children is four times higher than a full-time minimum wage job, and about three times higher than the poverty guideline.

One-in-six Louisville region workers live below 200% of the federal poverty line, which makes them eligible for different public assistance programs.

Cliff effects occur when workers become ineligible for public assistance programs due to a small increase in earnings. The additional income earned from taking a raise or a promotion may not be large enough to offset the value of the benefit that was lost. These cliff effects can cause a family’s financial situation to be worse off, even though they are earning more. Workers may choose to not seek career advancement because of the loss of resources.

The Family Resource Simulator shows the trade-offs workers face when they earn more, but lose work supports in the process. A single working mother with two children in Jefferson County faces several cliff effects as she earns additional income.

It is important for policy-makers and the business community to understand the issue of benefit cliffs, and how to soften their impact so that workers in low-wage jobs can progress along their career pathway without sacrificing resources for their families. Many states have implemented policy changes to address benefits cliffs.

Short-term solutions have primarily fallen into three categories:

Phasing out benefits slowing, creating a slope rather than a cliff

Raising eligibility limits, effectively moving the cliff to a point of higher earnings

Providing monetary incentives for continued employment or allowing more earned income to be retained

Long-term strategies aim to revitalize employment opportunities by:

Increasing educational and work supports through job-training and skill-development initiatives

Expanding educational funding

Asking employers to increase investment in early stage workers

Kentucky has taken an important first-step in the investment of creating the Family Resource Simulator. As policy-makers and the business community gain a greater understanding of the impact of benefits cliffs on the workforce, it is important to consider policy levers that can address these issues. The National Conference of State Legislatures has created this brief to serve as a guide.